Hat in Hand

January 9, 2024

It wasn’t invented in Texas, but America’s most iconic headwear is intrinsically tied to the state and its culture

BY: LAUREL MILLER

Manny liked to laugh and share a good story or two/If he’s making you a hat, he needs to know some things about you/He’d say, “Set yourself down, tell us what you’re thinking about/Your hat says something about you, before you even open your mouth.” –Jerry Jeff Walker, “Manny’s Hat Song

There are few things more identifiably and iconically Texan than the cowboy hat. It’s an image recognized around the world and indelibly linked to the Lone Star State’s history and culture, but the headgear owes much of its design to the vaqueros of Mexico and popular men’s styles of the mid-19th century.

In fact, the cowboy hat wasn’t even created by a Texan. John B. Stetson, founder of the eponymous hat brand now based out of Garland, Texas, was born in New Jersey in 1830. Stetson’s father was a hatmaker, which is where he learned the art of millinery. It was on a hunting trip in Colorado that the teenaged Stetson developed the prototype of the cowboy hat from a beaver pelt. He wanted a design that would provide protection from the high-altitude sun, as well as rain and wind, and the resulting topper had a wide, flat brim and a tall, open crown (meaning it had no creases or specific shape).

Although Stetson’s companions initially made fun of his outlandishly large creation, it was a chance encounter with a horseback stranger that led Stetson to sartorial success. The rider offered to pay Stetson five dollars for his hat and purchased it right off his head. Stetson moved to Philadelphia in 1865 to pursue hat making in earnest with the creation of his John B. Stetson company. His felt Boss of the Plains hat with its flat brim and high, domed crown, was modeled after that first Colorado prototype, which itself was derived from the straw sombreros worn by the vaqueros.

By the turn of the century, Stetson Hats was the largest hat company in the world, employing over 5,000 workers. Stetson was also ahead of his time when it came to worker’s rights, providing benefits like on-site housing, profit sharing, and health care. The Western icons of the day, including Buffalo Bill, Annie Oakley, Tom Mix, and later, Will Rogers and Roy Rogers all wore Stetsons.

Stetson as a brand and company was also instrumental in helping to change public perception about cowboys. Once seen as desperate, lawless characters who rustled cattle and robbed stagecoaches and trains, the Western films and television shows of the early to mid-20th century recast the cowboy as an uber-masculine hero- one who notably wore a white Stetson.

“Stetson is still synonymous with cowboy hats and culture,” says Tyler Thoreson, the company’s vice president of marketing. “The cowboy is a great American archetype, and a symbol of many of the things that make this country great: a belief in the value of a hard day’s work, a respect for tradition, reverence for nature, and the courage to follow your own path. Those are the values that have always defined cowboy culture and still inspire (our brand) today.”

In 1987, the Stetson company relocated its factory to Garland, Texas after it entered a partnership with Hatco, the largest manufacturer in the world (the company today owns Resistol, Charlie 1 Horse, and Dobbs). Garland also remains the epicenter of American cowboy hat manufacture, says Jerry Cook, president of Master Hatters. Jerry’s father, William C. Cook, founded the company in Garland in 1968 after decades of working under his mentor Harry Rolnick of Dallas’s Byer-Rolnick Hat Company. William was born in Haybank, Texas, and moved to Garland with Rolnick in 1938 when the latter relocated his company.

William’s first independent venture was manufacturing hats for Resistol Hat Company, but he eventually began to make his own line. After his death in 1977, his sons Jerry and William Jr. took over the company and today, Jerry’s son Matt is vice president. Jerry has hopes his grandchildren will one day join Master Hatters. “You have to know your history,” he says. “I grew up working for my dad and when he died, I had to make a decision. I pursued hats because it was mostly about keeping the family legacy alive.”

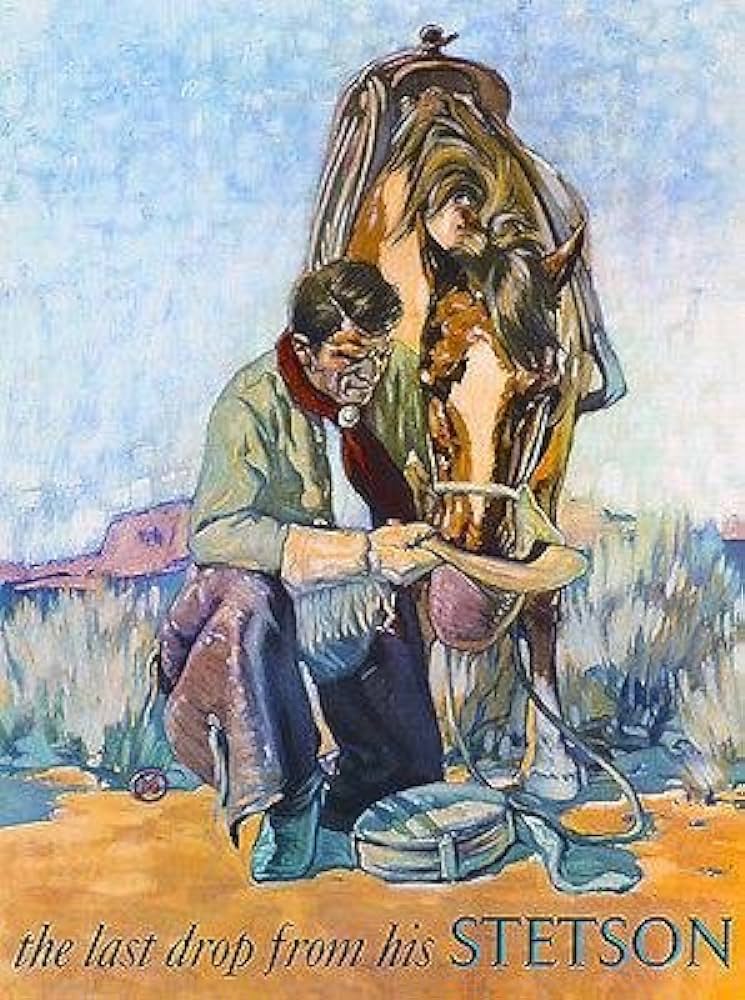

In 1912, famed Western artist/cowboy, Lon Megaree painted “The Last Drop from His Stetson,” an image that for over a century has captured the spirit of the American cowboy.

Even when there aren’t family members to take over the business, “you’re always trying to train the next generation,” says Jerry. “I’ve always called hat making a pseudoscience; it’s an art form that has to be managed through experience. It’s hard work. A lot of the younger generation would rather be on the computer, but 40 percent of our staff have been here for over 20 years.”

Master Hatters has 60 employees and produces 60 to 75 dozen hats a day, some of them private label products for other brands. “Stetson is our largest account; at one time, 67 percent of our business was making branded products for them,” says Jerry.

The company also makes its own line of high-quality shantung (a type of paper spun into yarn for hat making) and felt hats and more affordable wool hats, most of them for the same customer base Master Hatters has had since it started: cattle ranchers and professional rodeo folks.

Hats Off

Over time, “the cowboy hat underwent changes in shape to better suit the needs of its owner and evolved into the form we’re more familiar with today,” states the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum website. “The brim curved up on the sides to stay out of the way of a rope, and the crown became pinched to allow better control.”

While the Boss of the Plains was the first cowboy hat, made from the felted pelts of beaver, rabbit, and other small species traditionally used for their fur, different materials were eventually used to better suit the climate, including straw and palm leaf which provide better ventilation. Leather (primarily sheepskin) sweatbands and satin liners were added to absorb moisture, and the way a cowboy or cattle rancher wore his brim or hat crease came to serve as an indicator of what he did for a living.

“I’ve noticed that there are even different hat styles throughout Texas, depending upon the region” says Austin hatmaker Ras Redwine. “In South Texas, the brim is shorter, with more of a cowboy curl (see diagram, page TK); in the Panhandle, I see a longer, ‘taco’ brim, named for the shape. Bull riders had their own style for a bit, where the brim was narrowed toward the back, so the hat looked like it was on backwards. Styles are always evolving.”

Redwine is from a multigenerational cattle ranching family and runs his own small herd outside of Austin. He grew up in Amarillo and moved to Austin in 1993. He spent his summers working cattle on the family ranch as well as on ranches in the Panhandle, New Mexico, and near the Canadian River. Redwine came to hat making serendipitously after his best friend, hatmaker Chris Roberts of Aspen Hatter became a milliner, making high-end Western fashion hats.

Roberts started his hat company in Aspen, Colorado [it’s now located in Austin], and Redwine fell into helping him during visits. “I’d learned to shape hats over a teapot as a kid, but he walked me through the entire process, including teaching me to use a sewing machine,” he says. “I’ve always been artistic and worked with my hands, so hat making came very natural to me, which isn’t always the case.”

Redwine went out on his own in 2021, to better accommodate his primary vocation of cattle rancher. He currently only produces beaver felt hats (“If I could figure out how to make a day 48 hours, I’d love to get into straw.”), which start at $1,500 with a wait time of over a year (“I do think my customers respect that their hats take more time to make because I’m busy working cattle.”). Some of Redwine’s more notable clients include Matthew McConaughey, Pierce Brosnan, and Sylvester Stallone.

“There’s greater demand now for traditional cowboy hats, thanks to the success of TV shows like Yellowstone,” Says Redwine. “It’s like the Western craze of the early 80s, when Urban Cowboy came out. Because the industry has become very popular, pure beaver pelts are in short supply; it’s like trying to get concert tickets for a major show these days.”

Quality you can hang your hat on

When it comes to hat making, terms like “custom” and “master hatter” mean different things to different people. Jerry Cook considers Master Hatters a large custom manufacturer, because their product styles are driven by retailer demands. He thinks of independent hatmakers as “a different tier of custom. They make one hat a day, it’s like the sizzle on a steak; they beef it up with aroma,” he says, adding that Master Hatters maintains its commitment to using the highest quality materials and emphasizing superior customer service for individual customers and wholesale accounts alike.

Redwine agrees that “custom” can apply to different levels of hat making and believes that “bespoke” or “milliner” are more accurate terms for his work. “Commercial hatmakers aren’t milliners, that is, they don’t start out with a pelt (technically, the felted fur, also known as a blank, or body) and then fulfilling every aspect of the hat making process apart from actually hunting or trapping the animal.”

When Redwine makes a hat for a client, he starts by doing an in-person fitting in his home workshop. “I can do it over the phone but it’s not my preference,” he says, adding that “sizing is easy, it’s shape that’s most important. These are stiff hats that won’t conform to your head.” Redwine uses a conformer, an expandable tool that allows for accurate measurements. He then cuts and blocks the hat (shapes it over a wooden form) and sews in the sweatband and liner. The process requires a variety of tools, including different types of sewing machines, a crown iron, brim press, and brim cutter.

The final step is the hatband, which can take anywhere from two to 21 hours, depending upon the level of personalization required; some clients want to incorporate heirloom pins, found feathers, handwoven horsehair bands, and other items. The finishing touches include designs or initials stitched into the crown or providing an antiqued look. Redwine says that no two hats are ever alike, and the designs ultimately come down to an individual’s face shape, personal style, and attitude.

“I think that’s what attracts my customers besides staying true to the craft and maintaining the highest quality,” says Redwine. “For what it’s worth, I’ve been told I’m good at capturing a person’s style in a hat and each piece takes on a life of its own with the wearer. It’s a piece of art.”

While styles change and fads are fleeting, there’s no disputing the fact that the cowboy hat is here to stay. We live in an era of rampant urbanization and mass manufacturing, but here in Texas, the heritage and production of our iconic headwear remains true to its roots in companies large and small.

“Texans are so proud of their state and keeping that history alive is very important to us, but the shape of a cowboy hat also suits our lifestyle and for many of us, our vocation,” says Redwine. “When people all over the world think of Texas, they think of cowboy hats and boots. I’m grateful to my family’s ranching roots, because I wouldn’t be the hatmaker I am if I didn’t grow up that way.”

Hat tricks

If you’re in the market for a new cowboy hat, keep in mind the following tips from Jerry Cook, who has spent the last 46 years in the industry, and Ras Redwine, a sixth-generation cattle rancher.

- Visit a quality retailer and see what kind of service they provide. Happy, satisfied customers become repeat buyers.

- Shape is just as important as fit. Most retailers have lost the art of hat shaping, says Cook. It’s worth seeking out a specialist or paying a fee at a different retailer to ensure your hat suits your face shape and style.

- A high-quality cowboy hat should be very lightweight and fit snugly on the front and back of the head, with room at the sides.

- Choose your hat material based on personal preference, intended use, and budget. Wool hats, while less expensive, still retain a level of water repellence, but not as durable, and the fibers are likely to shrink if heated.

- Historically, “X” labels on hat models denoted the fur quality, but it varies according to manufacturer. For example, one company might use 4X wild hare/rabbit blend to indicate a mid-quality fur grade, while a 4X beaver hat could mean the highest quality felt for one company, 200X might be used by another. “To my knowledge, the X labels got a little out of hand and vague,” says Redwine. “The better terms to look for now are percentage of species, and different weights, which refer to the thickness and stiffness of the hair fibers.”

- “Rabbit fur is more textured than beaver, mink, or sable, with longer fibers, while beaver is softer, smoother, and more water repellent,” says Redwine. Beaver is generally considered the finest fur for hats and is sourced from the animal’s belly.

Fried Dove Breast Filets with Cream Gravy and Angel Biscuits

September 11, 2025

Hearty Venison Chili Recipe

September 11, 2025

Recap: 3rd Annual Knockout Clay Shoot with TWA

September 4, 2025

Dove Season Social: Turning Sport into Family Traditions.

August 8, 2025

Unique Ways to Make Money on Your Ranch

August 8, 2025