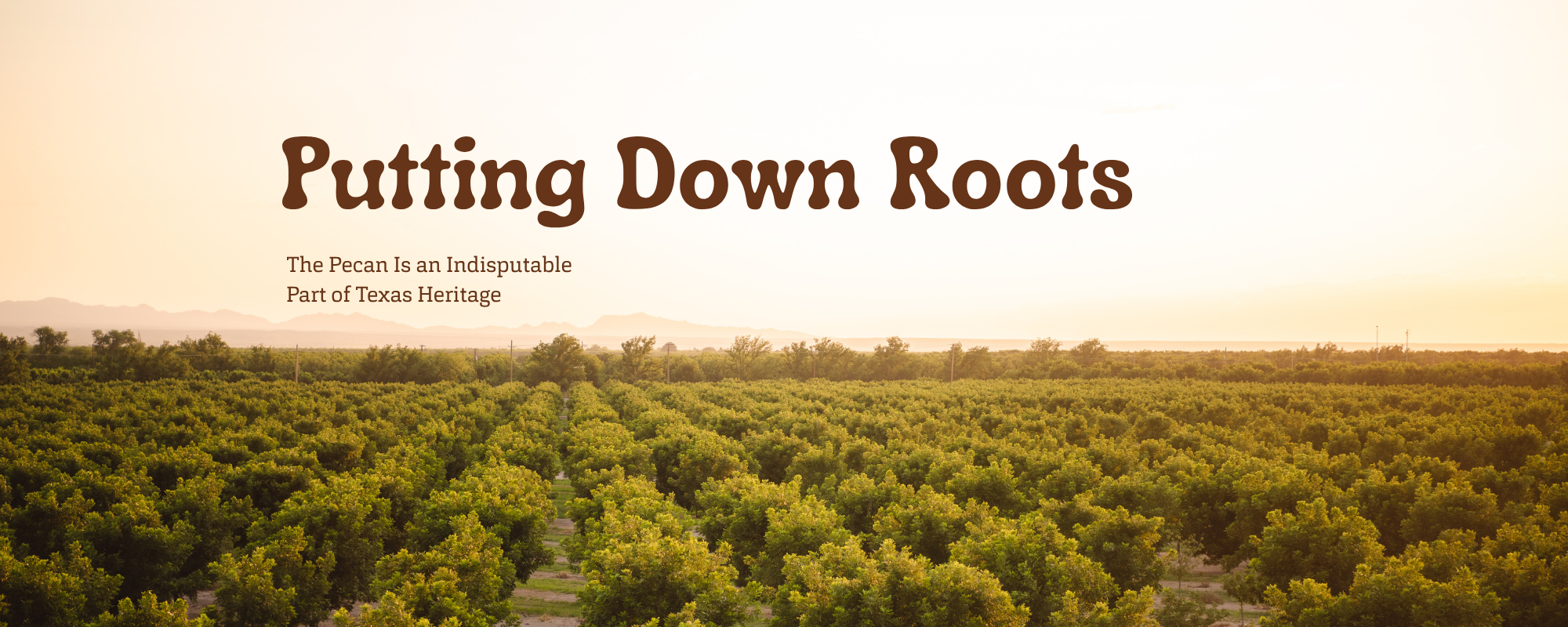

Putting Down Roots

June 4, 2025

By Laurel Miller

The pecan has- if you’ll pardon the pun- deep roots in the South and Southwestern United States. And, while Texas is the nation’s third largest producer of the sweet, buttery nuts, after New Mexico and Georgia, only the Lone Star State can claim it as state tree, a designation made in 1919.

“Texas is also the only state of the top three producers where pecans are a native crop,” says Blair Krebs, the executive director of the Texas Pecan Growers Association and publisher of Pecan South Magazine. “So many Texans have an emotional connection to pecans. For me, it was watching my grandfather hand crack shells while talking to the family or eating my grandmother’s pecan pie.”

Adds Kristen Millican of Millican Pecan in San Saba, “A lot of us grew up with a pecan tree in our own, or our grandparent’s yard, and pecans are also synonymous with the holidays in Texas. Those feelings of nostalgia have a way of creating traditions that are passed down.”

“A lot of us grew up with a pecan tree in our own, or our grandparent’s yard, and pecans are also synonymous with the holidays in Texas. Those feelings of nostalgia have a way of creating traditions that are passed down.”

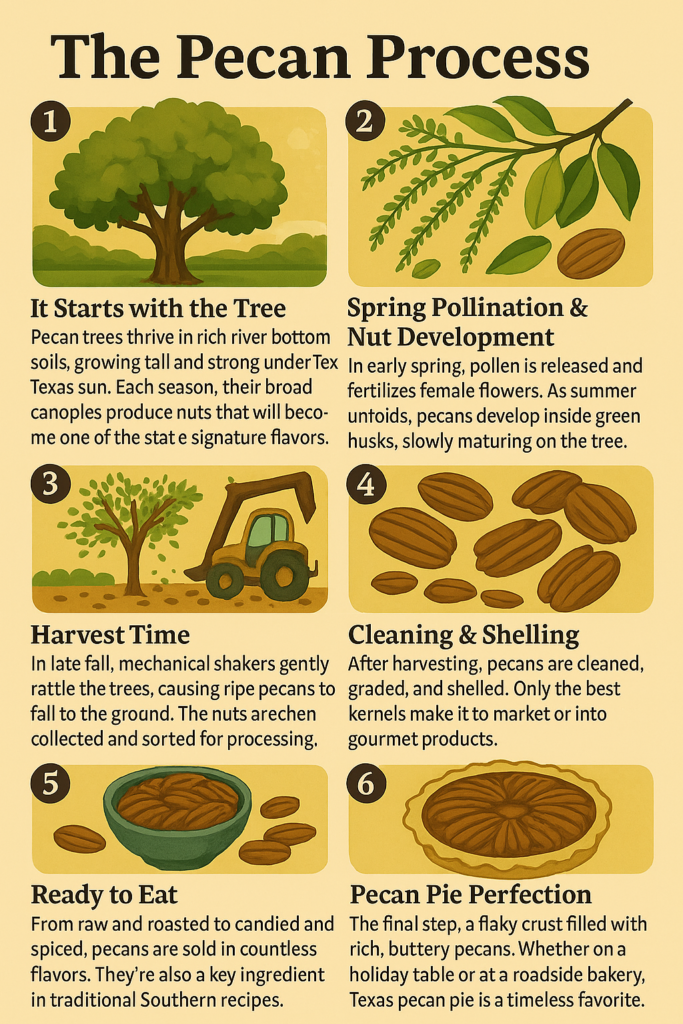

The pecan’s history in Texas predates mankind, however. In San Saba, the self-proclaimed “Pecan Capital of the World,” fossilized nuts from the banks of the Colorado River are estimated to be up to 65 million years old. The wild pecan trees (Carya illinoisnensis) currently found throughout parts of Texas can be up to 200 years of age; these native nuts are typically smaller and more intensely flavored than their modern hybrid counterparts.

Wild pecans were a crucial food source for early indigenous peoples like the pre-Columbian Coahuiltecan [the word “pecan” is derived from the Algonquin “pacane,” a nut necessitating a stone to crack its shell] of South Texas. Pecans were also an important source of trade amongst indigenous communities, which expanded their growing region: the continent’s “Pecan Belt” stretches from northern Mexico to northern Illinois.

While pecans aren’t the only major tree nut indigenous to North America, they are the only widely commercially cultivated native nut. According to Pecan Technology author C.R. Santerre, the earliest known plantings can be attributed to Spanish Colonists in northern Mexico. By the late 19th century, pecans were being propagated using grafting methods, in which rootstock from one tree is fused with a shoot, or scion, from another.

Pecans are also a sustainable crop. They’re wind pollinated, and have lower water needs than some tree nuts, such as almonds. Millican, whose family grows Pawnee and Cheyenne pecans as well as Natives, notes that the latter are the most sustainable type of pecan because they can withstand extreme temperatures and drought, and still produce a crop.

But, while pecans have grown in Texas “for centuries without human intervention, recent erratic and unpredictable weather and growing conditions puts more pressure on the modern management of pecan trees being able to produce a crop,” says Krebs.

Pecan pioneers

Pecans thrive in well-drained soil, which is why wild trees as well as orchards are often found in river valleys. In Texas, the Rio Grande River Valley outside of El Paso is the state’s epicenter of pecan cultivation, followed by Central and East Texas, with harvest occurring from roughly late September through early February.

Texas is also responsible for many of today’s most popular pecan hybrids, like the Choctaw, Pawnee, and Kiowa- varieties that have attributes like a higher oil content or larger size.

“The nuts with Native American names were mostly developed at the USDA ARS (Agricultural Research Service) stations throughout Texas,” says Krebs. “The Western variety, which is the most wildly cultivated worldwide, has direct ties to the Mother Tree in San Saba.”

The Mother Tree is estimated to be over 200 years old and according to Texas A&M’s Forestry Service, is “the source of more important varieties than any other pecan tree in the world.” It was discovered by E.E. Risien, an English cabinet maker who later purchased the land surrounding the tree and planted the first commercial pecan nursery in the county.

Today, Risien’s great-great grandson, Winston Millican carries on the family legacy of pecan cultivation. The fifth-generation grower owns Millican Pecan in San Saba with his wife, Kristen. The couple farm over 1,000 acres of pecans which are variously sold shelled, in-shell, or incorporated into pies, candy, and other specialty foods which are sold at the family’s farm shop.

A smarter way to farm

Climatic events in recent years have challenged Texas pecan growers. “Extreme drought and heat killed many trees, and the biggest issue our pecan farmers are facing is a downturn in the market including overall exports, which are sometimes filled by other pecan producing countries [primarily Mexico and South Africa],” says Krebs.

Input prices have also continued to rise, creating barriers for growers, while demographically, “most of our growers are older, and we don’t see many younger growers stepping up to replace them,” says Millican.

Younger generations sometimes opt out of farming due to the cost of rural land in Texas, which is compounded by a loss of agricultural land to urbanization and development. Pecan trees also take eight to ten years to produce, which means growers must have additional revenue streams in order to establish new orchards.

As a result, there has been an increase in pecan farmers implementing regenerative farming practices, says Krebs. Some of these methods include integrative pest management and the use of biochar, a carbon-based natural fertilizer that improves soil health and sequesters carbon.

For pecan grower Troy Swift of Swift River Pecans in Fentress, rising input costs combined with struggling trees led him to switch over to regenerative farming methods five years ago. He and his wife Athanasee grow 14 types of pecans as well as Natives. Their farm also has a small farm shop and sawmill for pecan and other hardwoods.

“Some of my trees were dying, and scientists couldn’t determine the reason,” says Swift, who began farming in 1998. “They thought it was due to the root stock or soil. As a result, I began studying soil health and asking questions. I also learned that I could use soil health as a countermeasure to drought.”

After a visit to pecan farmer Dennis Perz of Georgetown, Swift had an epiphany. “I could tell just by looking at his trees that something good was going on there. It was mid-summer, when trees are typically heat-stressed, and his weren’t,” he says.

After adopting some of Perz’s regenerative practices including amending soil using nitrogen-bearing cover crops, allowing native plants to grow on the orchard floor to bolster soil biodiversity, and making his own Johnson-Su bioreactor compost (a fungi-heavy enrichment that fosters biodiversity above and below the soil and increases water retention and carbon sequestration), Swift saw a dramatic improvement in his tree and soil health and crop yields.

Swift is also conducting experiments with biochar, humates, algae, compost, and wood chips, after chemical fertilizer prices skyrocketed. “I knew I had to find a smarter way to farm, and that meant working with Mother Nature, not against her,” he says. “We routinely have scientists come out to test the soil and do leaf analysis and nut nutrition analysis.”

The orchard uses a non-chemical biopesticide produced by Certis Biologicals as a form of integrated pest management (IPM), and Swift is also working with renown bat scientist Dr. Merlin Tuttle to identify species and bolster bat populations on the farm as a form of pest control. The bats feed on pests like mosquitos, roaches, termites, flies, and stinkbugs. In summer, barn swallows fly in the orchards. “I call the swallows the day shift, the bats the night shift,” says Swift, who is now an in-demand speaker on regenerative agriculture.

Despite the hardships, pecan farming remains firmly entrenched in Texas culture, and many growers remain committed to cultivating the nuts. “The majority of domestic pecan shellers (machinated nut crackers) are located in Texas, and most Texas consumers prefer products grown in-state,” says Millican. “The demand is strong. It’s a good place to be a grower for those reasons.”

For tour and farm shop information and online nut and confection orders, visit millicanpecan.com and swiftriveriverpecans.com.

Texas Tall Tales: Spooky Folklore and Legends That Still Haunt Us

October 14, 2025

Rice Farming: The Heartbeat of the Texas Coast

September 30, 2025

Fried Dove Breast Filets with Cream Gravy and Angel Biscuits

September 11, 2025

Hearty Venison Chili Recipe

September 11, 2025

Recap: 3rd Annual Knockout Clay Shoot with TWA

September 4, 2025